The Oversight Board: Facebook’s Self-Regulation with a Twist

Meet Facebook’s Oversight Board

As Facebook’s membership slowly inches towards 3 billion, content moderation is increasingly becoming a task riddled with legal and political pitfalls. The company strives to serve all the different types of users, cultures, and political systems that inhabit the platform, and failings have repeatedly brought Facebook under severe public scrutiny. In this vein, speculations about an independent adjudicating body to assist Facebook in its content moderation efforts have been brewing since 2018. Created in the U.S. Supreme Court’s image, the Oversight Board finally began its work in October 2020. The Board is external to Facebook’s existing content moderation system and its purpose is to provide an independent appeals venue for challenging content takedowns from Facebook and Instagram. Some view this arrangement as outsourcing, an effort to bolster accountability, or otherwise blatant buck passing. Regardless, today the Oversight Board has handed down 18 decisions, some of which have made news headlines internationally. In less than a year, the Board has instructed Facebook to reinstate a post criticising the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, approved the removal of a Zwarte Piet video in the Netherlands, and upheld the indefinite suspension of Donald Trump’s account following the Capitol Hill Riots. With the one-year anniversary of the Board fast approaching, this article will take a look at what this quasi-court represents and what it has achieved so far in the context of global content moderation.

The Oversight Board Taking Decisions

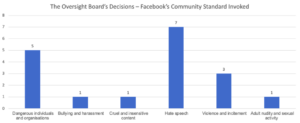

The Board is composed of 20 members, including academics, former politicians, and activists — a cultural and professional array to match the diversity of the Facebook community. Cases are submitted for review by Facebook or its users and concern previously removed content found to violate Facebook’s Community Standards and values. The Board exercises discretion in deciding what cases it will take on, keeping an eye out for the most “difficult, significant and globally relevant [cases] that can inform future policy.” A group of select members, whose identities remain anonymous, will then be assigned to a panel in charge of the review. In a balancing exercise between Facebook’s Community Standards and its human rights commitments, the panel must decide whether users’ rights have been adequately respected. During the deliberation process, the Board relies on the information provided by Facebook, the appealing user, and can even draw on insight from public comments and outside experts. For example, while reviewing Trump’s ban from Facebook, the Board received more than 9000 public responses. Upon review, the panel decides by consensus or majority to either uphold or reverse Facebook’s initial takedown. The Board’s decisions are binding, meaning that “Facebook publicly responds to the board and implements its decision, unless doing so could violate the law.” Additionally, the Board may also issue policy recommendations, which are not binding but provide guidance on Facebook’s future policy development.

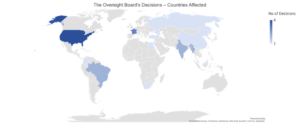

When asked what the Board is looking for when picking cases for review, current Board member and former Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt said the eye is on cases that have precedent-setting implications. Namely, she hopes key principles will be distilled from the Board’s decisions that can then spill over into Facebook’s automated or algorithmic content moderation. The Board is also determined to pick cases that come from all around the world and concern different Community Standards, such as hate speech, nudity, and COVID-19 misinformation. Therefore, in a year since its creation, the Board has amassed a diverse portfolio that speaks to its intentions of ensuring the free expression of all its users. The Board’s final decisions often include references to international treaties, commitments, and guidelines as well as the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which outlines the duties and responsibilities of companies in preventing human rights abuses. Such conduct is consistent with Helle Thorning-Schmidt’s statement: “Facebook and Instagram should be guided by Human Rights.” It must be noted that Facebook only “strive[s] to respect [human rights] as defined in international law” voluntarily. In light of such ambitions as well as the fact that its decisions cannot be appealed within Facebook’s internal process, it appears that the Oversight Board is the de facto final arbiter on what can and cannot be posted on the world’s largest social media network.

Questioning the Impartiality

The Oversight Board is arguably a unique phenomenon in the realm of online content moderation. It is a checkpoint external to Facebook’s existing review process, which inserts distance from Facebook’s business interests as well as an additional level of impartiality. To this writer’s knowledge, other social media platforms rely solely on an internal content review process. In fact, Thorning-Schmidt described the Board as “the only show in town” that demonstrates a different way of moderating online content. Nevertheless, a fair share of skepticism has been directed towards a Silicon Valley born and raised quasi-court that assumes to decide on international human rights norms. For one, the Board’s impartiality is consistently interrogated by critics and the public alike. The Oversight Board’s operations and its paid members are dependent on the $130 million trust fund established by Facebook. Although the irrevocable $130 million cannot be touched and should sustain the Board for an estimated period of six years, Facebook is not under the obligation to replenish the fund once it expires. Since Facebook’s Business Model is critically dependent on amassing user information to monetise, decisions to remove content may scare users away and thus sabotage Facebook’s core revenue stream. To pursue this further, the Board does not hold subpoena powers, which means that Facebook can always refuse to assist the Board in the review process. Even during the review of Trump’s suspension from the platform, which is arguably the Board’s most consequential decision, Facebook refused to provide answers to 7 out of the 46 questions submitted by the Board. This points at a skewed balance of power between Facebook and its alleged supreme court.

The Global and Regulatory Impact

Besides doubts on impartiality, the critics also question the Board’s ability to affect change and revolutionise global norms on content moderation. This is particularly the case since the Board’s decisions are tied to the cultural and political idiosyncrasies of the country where the problematic post was initially published. If the decision and principles that flow from it are country-specific, are they of true value to global content moderation? Unlike precedents established by courts of law, the Board’s precedent-setting power merely extends to “substantially similar” content and only if Facebook considers it “technically and operationally feasible” to remove. If Facebook were to adopt a conservative reading of future factual circumstances around problematic posts, then the Board’s views risk being forgotten altogether. Furthermore, what are the measuring sticks the Board uses when assessing freedom of expression in other countries? Surely, the limits imposed on free expression in the European Union are drastically different from those users in Russia or China face. In this context, the Board is assuming the authority to moderate content in authoritarian regimes, risking clashes between its interpretations and local laws. It is unclear which side will prevail.

In this case, perhaps it is best to leave content moderation to legislators – who have the impartiality and authority to create impactful rules on content moderation. In the same interview with POLITICO, Thorning-Schmidt argues that content cannot be reviewed in a courtroom, and while regulatory efforts are always welcomed, they must be accompanied by some form of self-regulation. According to Thorning-Schmidt, national legislation carries the risk of regulatory fragmentation. Countries where politicians adopt a heavy-handed approach towards content moderation, such as Russia, India, or Belarus, can effectively destroy the connectivity Facebook promises to its users. Preserving the integrity of the digital space is a precarious task indeed, and the legislators who are focused on the harmonisation of European Union law have an enhanced appreciation of this. For example, fears of a splintering digital market have been circulating around a French legislative bill on content moderation at the same time as the EU Digital Services Act (DSA) was under construction. Under its current format, the DSA calls for greater responsibilities and oversight to be imposed upon companies such as Facebook and their content monitoring practices. Once adopted, the DSA will be binding upon all EU Member States. In this context, the EU Commission warned the Member States against implementing “envisaged measures where these concern a matter covered by a legislative proposal in order to avoid jeopardising the adoption of binding acts in the same field.”

According to Thorning-Schmidt, the Oversight Board is able to circumvent discrepancies between national laws as it works towards preserving “One Facebook. One Instagram. One set of human rights that applies to everyone.” However, one cannot assume that the Board’s self-regulation efforts are resistant to the threat of fragmentation or that the Board itself will not cause regulatory fissures. It must be remembered that the Board operates in a very small playing field. For one, the Board is only presented with problematic content that Facebook initially deemed contentious enough to remove. In light of recently leaked company documents, it appears that certain elite users are insulated from Facebook’s review system and thus from the Oversight Board’s scrutinising eye. Moreover, the selection of cases that are brought to the Board’s attention must be further sifted through the Board’s eligibility criteria, which allow only for the most serious and globally relevant cases to be admitted. At this stage, the Board has analysed only a fraction of Facebook’s content, and its ability to significantly impact global content moderation is questioned.

Conclusion

The Oversight Board is an undeniably curious approach towards content moderation that deserves our attention. Facebook has been described as a tech titan for so long, it is refreshing to think that there may in fact be an overlord above Facebook itself. With a bold mission statement and international case catalogue, the Board has the potential to shape the standards of online monitoring. It is thus unsurprising that one of the Oversight Board’s members was named as one of POLITICO’s Tech 28 Power List in recognition of the Board’s role in deciding what can be posted on the world’s largest social media platform. However, we must still keep a critical eye on such magnanimous declarations of self-regulation from a company that feeds off data silos. The Board’s independence and overall ability to shape global content moderation are questionable at best. Significantly, even the Board’s claim over Facebook, the very entity it was designed to hold accountable, may be just as wavering. It remains to be seen how and whether the Board will own its powers, or whether it will be cowered into handling Facebook’s dirty work.

Madalina graduated from the University of Groningen with a degree in International and European Law. She is currently pursuing a career in online brand protection.

Featured Image: Shutterstock