German elections 2021: foreseeable trend reversal after sixteen years?

The votes are in

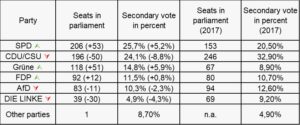

On Sunday 26th of September 2021, the German federal elections took place. The race had been enticing, but also surprising. Angela Merkel’s party, the CDU (Christian Democratic Union of Germany – conservative/right center) is facing after sixteen years of leading the government a historical low with 24,1% of the second votes (-8,8% on 2017’s result). Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (the Greens – climate-oriented/left), have put forward a chancellor for the first time and secured 14,8% (+5,9%) of the votes. The SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany – social/center-left) has also seen growth in voters, scoring 25,7% (+5,2%). For the slightly smaller parties such as AfD (Alternative for Germany; -2,3%) and DIE LINKE (The Left; -4,3%) losses were also noticeable. However, the FDP (Free Democratic Party) managed to achieve better results than in 2017 with 11,5% (+0,8%).

But first of all, how do German elections work? Germany is a federal parliamentary democracy, led by the chancellor. The system is notoriously complex; the country is made up of 299 constituencies, a minimum of 598 seats in the Bundestag (lower house of the federal parliament) and two votes per citizen. The first vote (Erststimme) is for the local MP. Candidates who win their constituency, based on a system of first-past-the-post, are guaranteed a seat in the Bundestag. To fill the other half of the 598 seats (or more), citizens cast their vote to a political party with the Zweitstimme, which determines the final percentage of seats each political party gets in the Bundestag. This year, the seats in the Bundestag have risen above 700, exemplifying the increasing number of voters splitting their votes, and thus increasing the overhang seats.

Source: Bundeswahlleiter, 06:00 MESZ, 27.09.2021.

Undeniably, this election marked the end of an era – an era that will be missed by many Germans and Europeans alike. The enduring fondness for Merkel is not surprising. She has been a seemingly unwavering, cool head throughout the past two decades of crises. Merkel has led Germany and Europe through the financial crisis of 2008, and the resulting sovereign debt crisis, the height of the European migration crisis in 2015, and, more recently, played an essential role in Europe’s response to the coronavirus pandemic. (If, you would like to know more about Angela Merkel‘s legacy, check out one of Shaping Europe’s other articles)

Before recapping the process of campaigning throughout the last months, we are first going to introduce who was running for the Chancellor’s office.

Annalena Baerbock for die Grünen

The largest green party in Germany is called Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. The name Bündnis 90 originates from a small party that was founded in the last years of the GDR. The color green already symbolizes what the party stands for: Nature and climate protection. Additionally, the Greens are concerned with human rights, the integration of refugees, as well as gender equality and a more social economy. During these elections, they opted for Annalena Baerbock as their main candidate.

Baerbock has been co-leading die Grünen with Robert Habeck since 2018. As die Grünen attach importance to promoting women in their party, Baerbock managed amongst other reasons to convince her fellow party members to choose her over Habeck. This was an important step not only for the party but also for the whole federal republic as she is the second woman in history to run for the position of head of government in Germany.

Still, it is important to mention that she is the only one of the chancellor candidates lacking government experience. Nonetheless, Baerbock has been active in politics for more than ten years, in her roles as the Spokeswoman of the federal working group Europe of the Greens (2008-2013), a board member of the European Green Party (2009-2012), the regional chairwoman of the Brandenburg Greens (2009-2013) and as a member of the party council of the Greens (2012-2015), she stands firm on topics such as climate protection and proclaims ambitious goals such as the prohibition of selling gasoline-fueled cars by 2030.

Armin Laschet for the CDU

The CDU is one of the largest parties in Germany, with over 400,000 members. It has a sister party, the CSU (Christian Social Union), which is only up for election in Bavaria, while the CDU can be elected in all other German states. In Germany-wide politics, the two parties form a common group. The CDU has been among the most involved in forming German governments after World War II. The party stands for a strong economy and low unemployment rates. Thus, they pursue pro-business policies. Christian values are also central to their policies. The CDU is considered conservative.

The CDU chose Armin Laschet as their candidate. Whilst Baerbock cannot bring experience in the German government to the table, Laschet can. Since 2017, he has served as Minister President of North Rhine-Westphalia. However, his way to the candidacy has been filled with obstacles. First, as an unwritten rule in the CDU prescribes, he has had to be appointed as his party’s chairman to run for chancellor, which he achieved in January 2021. This meant he had to prevail against his fellow party members Norbert Röttgen and Friedrich Merz. Second, after finally chairing the CDU, CSU leader Markus Söder wanted to be considered for chancellor candidate as well. The federal executive board of the party decided nevertheless against Söder and named Laschet as the official candidate. Given that generally the CDU‘s chairman is offered the position of chancellor, the board decided to stick with tradition.

Armin Laschet is a conservative Christian candidate who would continue Merkel’s policies. Despite the appearance of consistency with the outgoing Merkel, the CDU’s ratings throughout the campaign have suffered, implying that his persona in comparison to the other candidates, as well as his predecessor, is not as well received.

Olaf Scholz for the SPD

The SPD is also one of the largest and oldest political parties in Germany, with 420,000 members. It has been involved in the last two governments, forming a coalition with the CDU.

Its members are particularly concerned about justice for workers. This includes fair pay, secure employment and gender equality. They aim at a slight redistribution, especially the taxation of richer citizens, which could contribute to this in their opinion. This year, Olaf Scholz has been appointed their candidate for the office of chancellor.

Scholz has made a name for himself in German politics. He currently serves as vice-chancellor while holding the office of the republic’s finance minister. While the other candidates are all chairing their respective parties, Scholz currently does not due to his loss against fellow party members Saskia Esken and Norbert Walter-Borjans in an internal party vote two years ago. This is an important fact when considering that both chairs are more leftist-oriented than Scholz. Similar to Laschet, he would follow Merkel’s way of policymaking in case of a victory.

Scholz is being portrayed as a competent and experienced chancellor candidate in the media. German’s citizens appear to agree; the SPD has seen flourishing poll numbers during his campaign.

Campaigning Process

2021 has seen the German elections take a wild media rollercoaster – from the tragic flooding in July, where Armin Laschet let out a laugh at the most inappropriate time, during a press conference, to court ordered searches in Olaf Schloz’s finance ministry, to Annalena Baerbocks polishing up her CV whilst facing rightful accusations of plagiarism. Furthermore, at various instances ‘fake news’ and disinformation overshadowed the elections.

For example, soon after Baerbock’s entrance to the race earlier this year, posts appeared online claiming, falsely, that Baerbock wanted to ban children from having pets at home. While the absurdity of these claims is clear, genuine concern has been raised over the role of the media (traditional and new platforms) in disseminating falsehoods. Research by civil society group Avaaz on the topic even indicates that over half of all voters in Germany have been subject to at least one piece of disinformation on the Greens’ candidate. Further connections have been, and should be, made regarding the role of gender in increasing the likelihood of misinformation being spread about a candidate.

The opinion polls have also been a rollercoaster – three parties have at different stages taken the lead and, most importantly, no party has been forecast to win more than 25-27% of the vote.

This forecast has now been proven right, considering that the SPD won with ‘merely’ 25,7%. With these underwhelming numbers, the SPD as the winning party will be unable to put forward the next chancellor until a coalition with a governing majority is successfully built.

Which coalitions are likely?

Now that each party has finished pulling apart their opposition’s policies and discrediting their candidates, it’s time again to make friends, beginning the long process of building a coalition contract. The weekend the country was awash with Jamaican flags and traffic lights, as well as some other nicknames and colour codes for potential coalitions that could be formed in the coming weeks. Here are some of the options:

- The grand coalition – CDU and SPD: the combination of the Christian Democratic Union and the Social Democratic Party are regarded as the ‘safest’ alliance of the two largest, centrist parties. This coalition would represent somewhat a maintenance of the ‘status quo’, with Merkel leading this same coalition 3 out of her 4 terms, and every German state having experienced this combination at some point throughout their histories. However, Scholz has previously ruled this out, stating that his aim was to get the CDU to ‘rest’ in opposition.

- Jamaica – This combination represents a coalition between the CDU and CSU, as well as its third member – the Greens. This combination could be the most acceptable for the liberals. However, it is perhaps unlikely as the last attempt at this coalition in 2017 was put to an end with the FDP dramatically walking out over disagreements on climate and migration policy.

- Kenya – A coalition of the SPD, CDU and Greens could also be a possibility. This combination has previously governed in Brandenburg, though it would be a first on the federal level.

- Germany – This option would be the preferred choice for business leaders and high-income earners. This coalition refers to the CDU, SPD and FDP.

With the results as they stand, it is likely that a three-party coalition will be necessary to achieve a governing majority. In the coming weeks we will observe the results of a series of ‘exploratory talks’, as the parties decide with whom they are able to work together. The newly elected parliament must hold its inaugural session on October 26.

Expectations for the new German government and implications for the European Union

Germany remains one of the most powerful EU countries, due to it being the most populous and economically powerful state. Hence, it is essential to know what role the EU will play for the new leading party as well as the respective coalition.

In an article from the Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (a public broadcaster in Germany) written by Matthias Reiche, MEP Peter Jahr is quoted as saying:

“There are many important decisions to be made in the European Union, such as: How do we shape the fight against climate change? How do we position ourselves in global competition?” His remark summarizes some of the important questions, which could be answered differently depending on which party will be in the lead of the German government.

For example, the EU has been very active in its climate policy in the framework of the Green Deal. During the pinnacle of the COVID-19 crisis, other policies moved to the front, while now that the crisis abates more or less, the Green Deal is back as a main priority of the Commission, as announced by von der Leyen during her speech on the state of the union two weeks ago. Consequently, Germany’s new lead party and its commitment to tackle climate change is of the utmost importance to the progress of the union itself in that policy area. On a side note, one has to acknowledge that all three parties address climate change policy in their program and mostly agree that it’s a pressing issue. If the CDU or the SPD takes the lead in the elections, less stringent policies in favor of the climate will be produced. Climate neutrality is envisaged by both parties for 2045 and greenhouse gas emissions should be reduced by 65% by 2030. Whereas if the Greens secure the most votes or coalesce with the winning party, green policy will be at the center of German politics and therefore a priority in EU politics as well. They aim for climate neutrality by 2035 and opt for a reduction of 70% with regard to emissions. With green policy at the helm, Germany has the potential to significantly drive negotiations on the EU level on topics such as deadlines for the production of emission-producing cars, EU-wide installation of infrastructure for emissions-free cars, as well as defining common CO2 prices.

Similar expectations lay within Germany’s orientation with regard to EU foreign policy after the elections. All parties (SPD, CDU, die Grünen) are clearly pro-EU and tend to favor European integration. Still, the SPD and die Grünen promise to deliver more ambitious policies than the outgoing CDU-led government in that regard. Also in the field of digitalization, die Grünen and the SPD seem eager to initiate more sustainable change than the CDU has tried to achieve in the last decade.

Will the European Union be able to achieve a new momentum in terms of realizing strategic autonomy in trading terms? Especially, since the EU itself wants to be seen as a global player without having to solely rely on the US, Germany’s commitment towards that goal could give a much-needed incentive. With the CDU or the SPD winning the elections, minimal changes in the EU’s foreign trade policy practices will take place. Both parties tend to refrain from positioning themselves when it comes to aligning either with the US or China. However, if die Grünen make the cut, strategic autonomy is to be considered more likely. Especially because the European value of human rights is of utmost importance in green politics, a stricter tone might be expected within Germany and therefore EU foreign policy, if a third country disregards these European values.

Now that the SPD has secured most of the votes, with only a small advantage on the CDU, it remains quite open who will lead the coalition to follow. The FDP and die Grünen will be the first ones to meet for exploratory talks. If they agree to cooperate and then choose either the SPD or the CDU depending on the offered terms, the coalition process would be given a whole different momentum. This would definitely provide for the aforementioned trend reversal in the sense that the big two people’s parties (SPD and CDU) will play a less powerful role in the coalition building than expected. One thing is for sure, the longer this process will take, the less impetus for Europe is to be expected in the meantime given that no government means no progress.

Niamh has obtained a degree in international relations from Monash University in Australia and has just finished her double masters degree in European Governance at both Utrecht University and Konstanz Universität.

Sandra Zwick has previously obtained a degree in Economic Sciences and Japanese Studies from Martin-Luther-University Halle/Wittenberg. She has recently graduated with a dual Master’s degree in European Governance at both Masaryk University and Utrecht University.

Image: Shutterstock