The Sámi: Indigenous lands in Europe

The land rights of the Sámi over their traditional territories.

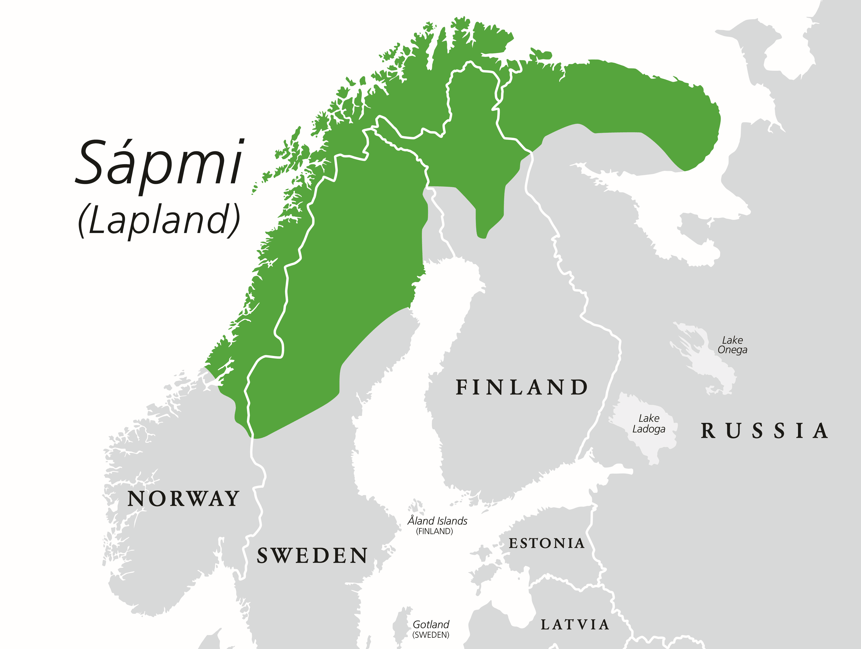

Discussions about Indigenous communities and their rights often feel like a world away for Europeans. We hear about it from countries like Australia and the United States, or it comes up when discussing the rain forests of South America. What a lot of people do not know is that there is also an Indigenous community in Europe, with a population estimated to be about 80,000 people. I am referring to the Sámi, a (semi-)nomadic people that live in Sápmi. This region spans the northernmost parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the Kola Peninsula in Russia. The term ‘Indigenous’ refers to a distinct social and cultural group of people native to a specific region. They have collective ancestral ties to the lands and natural resources and lived there before the arrival of colonists or settlers. In this article, special attention will be paid to the rights the Sámi hold over the territories they traditionally occupy.

The Sámi

The Sámi have lived in Sápmi for as long as our memory reaches. Sápmi refers both to Sámi land and Sámi people. The word Sámi itself means ‘people of Sápmi’. The herding of reindeer is an important part of the Sámi livelihood and culture and it is the reason that a part of the Sámi population practices a (semi-)nomadic lifestyle. Besides that, their livelihood consists of hunting, farming and fishing. The natural environment of the Sámi has thus always formed an essential part of their identity, and it is therefore not surprising that Sámi law embodies respect for their surrounding environments. Customary law is a set of laws based on traditions, customs and/or norms of a certain community. The customary law of the Sámi is strongly based on their way of life. In addition, the customary law relates to sieidi (natural sacred sites). Traditional rules that concern offerings or rituals are recognised by the Sámi as customary law or eternal natural law. Studying Sámi law without paying attention to cosmology and elements such as environment, balance and sustainable development is therefore impossible.

An important establishment in Sámi society is a village assembly called siida. This establishment plays an important role in the distribution of natural resources and land. The outline of the assembly depends on the livelihood of the Sámi society in question and the structure of the siida differs between different regions. Customary law regarding land emerged both within and between the siidas. For example, siidas have their own seasonal pastures and migration routes, which are thoroughly described and mapped. That does not mean that the siidas are static units. Incidents and encounters with members of other siidas or animals, landscape or weather can influence their formation, therefore causing siidas to be continuously subject to change.

A map of Sápmi

During the past few centuries, many Indigenous peoples have faced discrimination, oppression, assimilation or even genocide. The Norwegian government has carried out a policy in the past that aimed for the ‘Norwegianisation’ of the Sámi living in Norway. This policy of assimilation lasted for more than a century. Nowadays, violations of the fundamental rights of Indigenous peoples still occur. For example, the Norwegian Supreme Court ruled in 2021 that wind turbine developments violated the rights of Sámi reindeer herders. The Norwegian government had ignored that the turbines were located on the land of the Sámi people. In the past decades, Indigenous rights have gained more attention, spurring the development of new jurisprudence and doctrine from both international and regional institutions. Despite these developments, the rights to land and resources of many Indigenous peoples are still not recognised, meaning they do not hold official rights over their lands. Because the Sámi have an oral history, they have no written deeds to their lands that can prove ownership. That is why their land rights are based on the traditional occupation of their territories since time immemorial. Sometimes it is difficult to prove this occupation or the State does not want to acknowledge the right to certain territories because of economic motives. Both states and private actors have posed threats to the presence of Indigenous peoples on their traditional lands. Adding to the pressure are global trends such as ‘land grabbing’, or the appropriation of land for projects such as wind farms, and the exploitation of natural resources such as minerals.

The Lapp Codicil

The oldest legal document on Sámi rights is the Lappkodicillen (or Lapp Codicil) of 1751. The Lappkodicillen is an addendum to the Strömstad Treaty of 1751 between Norway (which then included Denmark) and Sweden (which then included Finland). The Strömstad Treaty defined the border between Norway and Sweden. The Lappkodicillen concerned the nomadic Sámi reindeer herders, as this was the major cause of cross-border migration between the two countries. Article 10 of the Codicil stipulates that Sámi may cross the border, and specifies when and how. The document acknowledged the established customs and practices of the Sámi but did contain certain constrictions for them. For example, according to the treaty one could only hold tax lands in one country. Sámi had to choose whether to become Swedish or Norwegian citizens and thus where to pay taxes and hold land.

Nowadays, the Lappkodicillen of 1751 is still relevant, both in real and symbolic terms. New legislation regarding the cross-border rules for Sámi reindeer herders has been implemented. The most recent example is a convention between Sweden and Norway on reindeer grazing in 1972 which expired in 2005. Reportedly, negotiations for a new cross-border reindeer herding treaty are ongoing, but in the meantime the Lappkodicillen is the main legal document on this issue.

European Court of Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) was drafted in the aftermath of the Second World War and also contains anti-discrimination provisions, primarily aimed at the discrimination of minorities. The ECHR applies to the Sámi. It is challenging for them to bring a case before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) as it is limited to legal texts like the ECHR that did not take Indigenous peoples into account.

Furthermore, the human rights system of the EU has used the term ‘Indigenous’ in ways that break with the modern sense of the term. For example, in several cases the term Indigenous was used to refer to the majority population as opposed to immigrants or foreigners. Indigenous issues have played a limited role in case law of the ECtHR. In contrast, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) has made several decisions regarding Indigenous rights and has addressed the needs of Indigenous communities. Because of this the court is described as extremely progressive and ahead of the ECtHR. Admissibility is another issue for Indigenous peoples who want to bring a matter before the ECtHR. Applications must be filled out in the leading official language of the member state. This is problematic considering the fact that access to education to (usually remote) homelands of Indigenous peoples is often limited.

The Finnmark Act

The Finnmark Act of 2005 regulates the rights to land and natural resources in Finnmark, which is the most northern county of Norway and has a larger surface area than Denmark. This is also the county with the largest Sámi population; namely one-quarter to one-third of the population. Similar legislation has not been implemented in other Sámi-inhabited regions. The Act is a one-of-its-kind in Norway in the sense that both the Sámi Parliament and the Finnmark County Council were involved in the negotiations. The Finnmark Act can be placed in a broader trend of growing awareness regarding the Sámi, alongside the introduction of the Sámi Parliament, Sámi Law Commission and Sámi Cultural Commission.

The most impactful aspect of the Act is the establishment of the Finnmarkseiendom (the ‘Finnmark Estate’ or FeFo). The FeFo owns and manages the public lands in Finnmark. The FeFo is ruled both by the Sámi and Finnmark’s general public. Legally, it is a private law body to protect Sámi ownership of land in the region. From a political point of view, however, it is a governing agency that carries out control over Finnmark between the Sámi and other Norwegians through a form of shared rule. Consequently, the FeFo has substantive decision-making power over land and resources. Some argue that, although it does enhance Sámi rights, this is impaired by the fact that all rights are non-discriminatory, meaning that there is no distinction between Sámi and non-Sámi in the region. Therefore, the Sámi have no clear ownership rights over the land as a means to engage in their traditional livelihoods.

The Sámi flag

Sámi Parliaments

The representative organizations of the Sámi are called Sámi Parliaments – Sámediggi in Northern Sámi – and are established by law. Internationally, the Sámi are represented by the Sámi Parliamentary Council (SPC), established in 2000 as the coordinating body for the three Sámi Parliaments in Norway (1989), Sweden (1993) and Finland (1995), and as a representative for the Sámi civil society. There also exists a Sámi Parliament in Russia, which is not recognised but does have representation on the Sámi Parliamentary Council. The legislation, funding and tasks of the Parliaments differ depending on the country. Certain administrative tasks have been transferred to the Sámediggi since its establishment. For example, in Sweden, it is the central administrative agency for reindeer husbandry.

There is, however, criticism regarding the amount of self-determination of the Parliaments. The reason for this is that the Sámediggi obtained legal status as a government agency, which allocated them a place within the national government and with a limited mandate. For instance, in Bill 1992/93:32, passed by the Swedish Parliament, it is clearly stated that “the Sámi Parliament was not a self-governing body that should function in place of the Swedish Parliament or Swedish State’s municipalities or to compete or conflict with these organs in powers or decision-making.” Thus, they mainly serve an advisory function.

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has found that Finland violated an international convention on racial discrimination when it comes to the political rights of Sámi. The breach can be traced back to a discussion concerning who may decide who is Sámi. Many Finnish Sámi believe that they alone should be able to decide who is Sámi and who is not. The case itself concerns the 2015 Sámi Parliament elections and an opinion of Finland’s Supreme Administrative Court stating that dozens of people who identified themselves as Sámi should be added to the electoral roll and, therefore, be eligible to vote in the elections that year. This constitutes a breach of the Sámi’s right to self-determination. This view was endorsed by the UN committee, which identified the people in question as Finns, seeing that they did not have any strong affiliation with Sámi identity and culture.

Free, prior, informed consent

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 2007 (UNDRIP) is a very important international instrument dealing with Indigenous people’s rights. According to Article 19, states shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the Indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions to obtain their free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them. This must be read in conjunction with Article 32, which sets out the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of Indigenous lands. FPIC can be seen as a fundamental right in the development process, therefore relating to the right to self-determination. The FPIC obligation ensures that when activities take place on Indigenous lands that may negatively affect the community, they are not threatened or pressured, their consent is sought and it is freely given based on all of the relevant information well before the activities take place.

In practice, an issue arises when states claim FPIC is inapplicable when launching or authorizing development projects on Indigenous lands under the guise of their right to control natural resources for national development goals. The flexible approach to FPIC that can be found in Article 32 confirms that FPIC is also required when these activities may negatively impact Indigenous peoples. This has been confirmed by the IACtHR. FPIC has not (yet) appeared in any decision of the ECtHR and is also not featured in European regional treaties. The FPIC is, in practice, often breached when states and/or private companies have interests in minerals that are located on Indigenous grounds or want to start projects relating to renewable energy.

Although the Sámi have gained a stronger position in the past few decades, a lot of progress has to be made. The recognition and respect of their land rights are essential to safeguard their rights and will be extra important with a view to the threat of renewable energy projects, mining, logging and climate change. These threats will be further discussed in a future article.

Julia is studying Notarial Law at Utrecht University. She is also studying Liberal Arts and Sciences, with a major in International Relations in Historical perspective.

Images: Shutterstock