Country profile Romania: A year of elections

Keep the current course or go in a different direction?

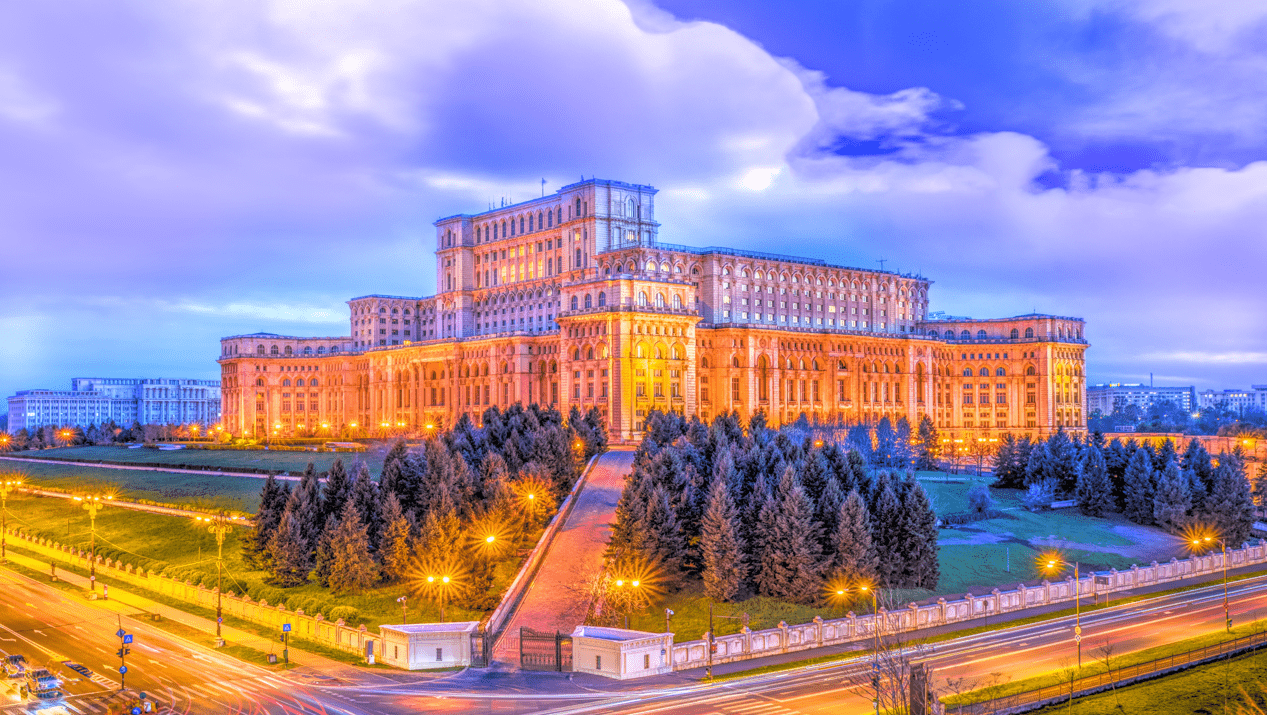

Romania, the land of Transylvania and Dracula. The homeland of Francesco Illy, the inventor of the espresso machine, and Nadia Comăneci, the first gymnast ever to score a perfect 10 at the 1976 Olympics. Where you will find the world’s heaviest building at a whopping four million tonnes in the capital Bucharest, namely the Parliamentary Palace. The country with the first city in Europe to be lit by electric street lamps and also the country where as many as six thousand brown bears live out of the total 200,000 worldwide.

Romania in brief

The name ‘Romania’ comes from the Latin word “Romanus”, meaning “citizen of the Roman Empire”. The southeastern European country was occupied by troops of the Soviet Union army in 1944 and became a satellite state of the Soviet Union from 1948 to 1989 until the regime of Romanian leader Nicolae Ceaușescu was overthrown. The first free elections followed a year later – in 1990. In 2004, the country joined NATO, and membership of the European Union (EU) also followed in 2007. On 31 March 2024, Romania will join the Schengen area, making travelling abroad even easier for Romanians.

At the time Romania joined the EU in 2007, the country was not quite ready to join, as it was still lagging in terms of reforming the rule of law and fighting corruption. For this reason, after accession, Romania was monitored by the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM) to catch up with the rest of the EU. In September 2023, the European Commission decided to close the CVM as they believed Romania had fulfilled all its obligations.

There are currently 33 members representing Romania in the European Parliament. In the European Commission, we find Adina-Ioana Vălean, who is the Euro Commissioner for Transport on behalf of Romania. Not a bad choice when you consider that Romania ranks 15th in the list of countries with the most extensive railway network in the world.

Over 19 million people currently live in Romania but the population is declining rapidly. More than five million Romanians have left their homeland since the fall of the communist regime in 1989. EU membership has only intensified this process, resulting in severe labour shortages in some sectors. Schengen accession will make it even easier to travel to other countries, with the risk that more Romanians will leave their homeland.

Romania’s national politics

Romania is a semi-presidential republic with a head of government – the Prime Minister – and a head of state – the President. The Romanian government consists of a Prime Minister, a role currently filled by Ion-Marcel Ciolacu, and his ministers. Under the Romanian constitution, the President has a more symbolic role, is responsible for foreign policy, approves bills from Parliament and nominates the prime minister. Currently, Klaus Iohannis, who has also applied to become NATO chief, fills the role of President.

Romania has a democratic multiparty system, with the government and the two chambers of parliament holding legislative power. The Parlamentul României consists of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. Members are elected every four years according to a proportional electoral system. There is a total of 466 seats – 136 Senators and 330 Deputies.

The Parliamentary Palace in Bucharest

The country is divided into 41 districts and the municipality of Bucharest. Each district is governed by a county council, which is responsible for local affairs. There is also a prefect – an administrator – responsible for implementing national politics at the county level.

Romania’s current government is led by a coalition consisting of the Partidul Social Democrat (PSD) and the Partidul Naţional Liberal (PNL). There are quite some tensions within the coalition due to conflicting policy objectives. The socialist PSD would like to impose higher taxes on the private sector, while the PNL opposes this as it would lead to less investment in the country – and thus in Romania’s economic development.

2024: the year of elections

2024 promises to be a busy year for Romanians, with as many as four different elections. The election year will kick off with the European Parliamentary elections on June 9, followed by local elections. As if that were not enough, the presidential and parliamentary elections will also take place at the end of the year. Looking at political shifts in other countries, including Sweden, Italy, Slovakia and the Netherlands, the upcoming election year is important not only for Romania itself but also for the EU.

The parties of the current coalition, the left-wing PSD and centre-right PNL top the polls with 30% and 19% of the votes respectively. However, as in many EU countries, the far-right is also on the rise. Indeed, the PNL is engaged in a neck-and-neck race with the ultra-nationalist opposition party Alliance for the Unity of Romania, also known as AUR, which is the Romanian abbreviation for gold. It is expected that although AUR will grow significantly, the party will not be able to form a coalition. However, if the national elections of recent years have taught us anything, it is that nothing is decided just yet.

In December 2020, the then relatively unknown AUR received 9% of the vote overnight, even though the party had only been founded in October 2019 by former journalist Claudiu Tarziu. Since then, the party has been growing steadily in the polls. The growth can partly be explained by the support the party receives from the Romanian diaspora, which largely consists of low-skilled workers doing a lot of seasonal work abroad. This group has no representation in Romania’s political system, where the same coalition has been in power for almost a decade.

The AUR presents itself as a party that stands for values such as family, the nation, faith and freedom. Critics, however, believe that in reality, the party has a programme that looks at science with distrust and where Christian fundamentalism is central. The latter can be seen in 2018 when Tarziu wanted to hold a referendum on banning same-sex marriages. In addition, the party portrays itself as an anti-corruption party, bringing in many votes from citizens frustrated with the country’s political instability and ineffectiveness. This is not a far-fetched idea when you consider that Romania is one of the worst-scoring EU countries when it comes to tackling corruption according to the Corruption Index. As recently as September last year, Dumitru Buzatu, a local leader of the PSD, was caught taking bribes.

Some 70% of Romanians are dissatisfied with how the country is currently governed. There is much disagreement within the current coalition on how to tackle economic problems and struggles to keep public finances under control. This leads to declining confidence and opens the door for alternative parties such as the AUR.

Popular discontent also manifested itself in massive protests in spring 2023 when over 150,000 teachers and another 70,000 teaching assistants took to the streets to demand higher salaries. Although the government partially succeeded in meeting the demands of education staff, people from the healthcare and police sectors also organised protests out of dissatisfaction with low pay. The big problem for the Romanian government is that its spending on the public sector is much higher than its revenue, so higher salaries cannot be paid.

The 2019 European Parliament elections

In the 2019 European elections, only a portion of all Romanians eligible to vote turned up at the ballot box (51.20%). While this does not seem like a lot, it is more than the EU-wide average turnout of 50.66%. What is striking is that the number of voters has increased enormously compared to the 2014 elections, when the turnout rate was around 30%. What exactly is the reason for the substantially higher turnout is not entirely clear, but it possibly has to do with the discontent that prevailed in Romania in 2019, with many voters mostly casting their vote against a specific candidate or party, in this case notably against the PSD.

Generally, during European Parliamentary elections, political parties focus on campaigning among the population of their own country. However, during the 2019 elections, Moldova played a big role for Romanian politicians. Now I hear you thinking – Moldova is not a member of the EU, is it? That’s right, but Moldova is home to more than 600,000 Moldovans who also hold Romanian passports and are therefore allowed to vote in European Parliament elections. If you consider that the total Moldovan population consists of around three million people, that is quite a sizeable proportion. Right-wing political parties, in particular, are pushing to recruit votes among Moldovan Romanians. The main focus is on promising to help Moldova on its way to EU membership, or on promoting the reunification of the two countries.

In the last European elections, the PNL became the largest, closely followed by the PSD and the liberal coalition of Save Romania Union (USR) and Romania Together. Although the social democratic PSD still gained a nice number of seats – eight in total – it did mean a halving of the number of seats compared to the 2014 elections. Many of those seats went to the USR coalition instead. The entire overview of the 2019 elections can be found below:

| Party | Number of seats |

| PNL – Partidul Naţional Liberal (EVP) | 10 (27,0%) |

| PSD – Partidul Social Democrat (S&D) | 8 (22,50%) |

| USR+PLUS – Save Romania Union & Romania Together (RENEW) | 8 (22,36%) |

| Partidul Pro Romania (S&D) | 2 (6,44%) |

| PMP- Partidul Mișcarea Populară (EVP) | 2 (5,76%) |

| UDMR – Romániai Magyar Demokrata Szövetség/Uniunea Democrată Maghiară din România (EVP) | 2 (5,26%) |

| ALDE -Alianța Liberalilor și Democraților | 0 (4,11%) |

| Other parties | 0 (6,57%) |

The upcoming European elections: What can we expect from Romania?

The European People’s Party (EPP) is expected to lose many Romanian seats in the European elections in June, while the right-wing group of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) will gain more votes from Romanian voters. According to polls, the AUR could ensure that six of Romania’s 33 seats in the European Parliament go to the ECH. This would also make it the first Romanian seat for that group.

However, the AUR is not the only right-wing party that will participate in the elections. Three Romanian parties – the USR, Forța Dreptei, and the PMP – have decided to form the United Right Alliance together to fight the PSD and the PNL in the European elections. The first eight candidates to appear on the voting ballot have already been announced, including former USR president Dan Barna and former health minister Vlad Voiculescu.

In addition, current MEP Nicolae Ștefănuță will campaign independently for the “green family in Romania” after he quit the Renew group last year and joined the Greens. Ștefănuță believes the current Green party in Romania, Verzii, lacks credibility and is embroiled in an internal power struggle. He hopes to create more space for green politics in Romania, an element that is virtually non-existent today. He wants to do this by focusing on youth and issues that affect them, including unemployment, housing, mental health and climate change.

What will happen in June, during the European Parliament elections, cannot be predicted at this stage. What is clear is that 2024 is an important year for Romania’s future. With all the elections still to come, the country may take a different path. Whether this will happen, we will see this year, when Romanians, including those living in Moldova, go to the polls.

Sabine Herder has a master’s degree in Crisis and Security Management from Leiden University and is now doing a master’s degree in European Policy at the University of Amsterdam. Before this, she did a bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a major in International Relations.

Images: Shutterstock