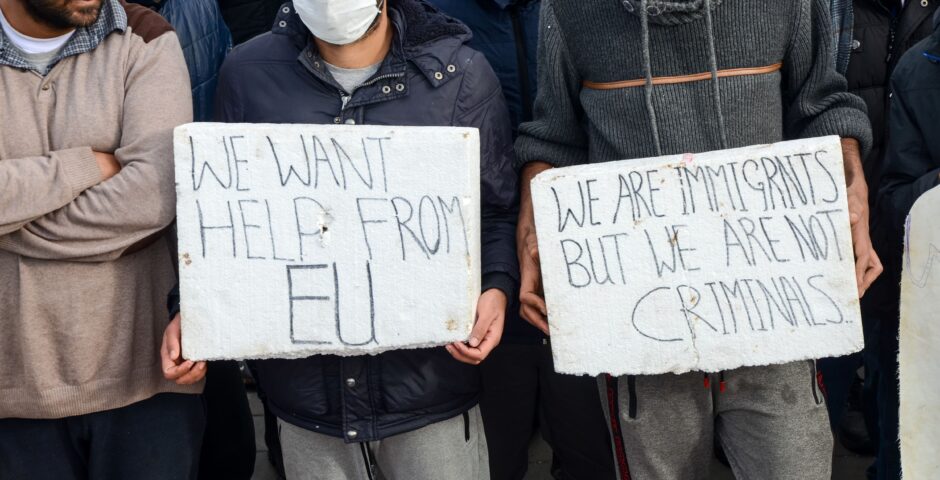

Transnational Party Lists: What would be the impact of it?

A More European European Parliament?

Imagine that you are about to vote in the European Parliament elections and participate in an expression of democracy along with others across 26 other countries. However, instead of only being able to vote for party lists to help determine how your country’s European Parliament seats are allocated, you can also vote for a party list that consists of candidates from across the whole of the European Union (EU).

This idea of introducing transnational party lists has been around since the 1990s. It aims to help create a more democratic European Parliament which allows for more pan-European Union-focused perspectives. However, the idea has also been criticised for going against member states’ national sovereignty and being incompatible with the existing forms of national representation within the EU. It is worth then having a look at both the movement for transnational party lists and the arguments against their introduction to better understand if such a change would result in a more ‘European’ European Parliament.

History of the movement for transnational party lists

The idea of transnational party lists has roots in the 1990s. The 1998 Anastassopoulos Report from the European Parliament raised the idea of 10% of Members of the European Parliament being elected from transnational party lists. What does this mean though?

According to a 2018 article by Renew Europe (one of the groups within the European Parliament), transnational lists would not replace national lists but would exist alongside them. Therefore, voters would be able to vote for 2 candidates – one from their national lists and one from their transnational lists. The transnational lists will be formed by the different groups within the European Parliament and will contain candidates from across the European Union. The different groups from within the European Parliament will compete against each other for a share of seats within the European Parliament set aside for transnational candidates.

For example, in a European Parliament election where transnational party lists are used, you would be able to vote from both a national list and a transnational list. The national list would be made up of national parties from within your own country. For example, a Dutch voter would be able to vote for GroenLinks, D66, or VVD while a French voter would be able to vote for La République en Marche, Rassemblement National, or Les Républicains. Both voters would also be able to vote for one of the groups within the European Parliament, making up the transnational party list. The Dutch voter could vote for the European People’s Party while the French voter could vote for Renew Europe. The candidates from these lists would be put forward by these groups and could likely not be from the voter’s own country. So, voters will be able to vote both for national representation and greater European representation of their political opinions within the European Parliament.

The idea of transnational party lists remained as just that – an idea – throughout the 2010s and currently the early 2020s. The usage of transnational lists was repeatedly suggested from 2011 to 2013 through the Duff report, created by a British member of the European Parliament. This report was never voted on however due to not having enough support within the European Parliament, due in part to the European People’s Party. Following the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU due to the Brexit Referendum, the question of what to do with the 73 British seats in the European Parliament was raised. In January 2018, southern EU countries and Ireland expressed support for the idea of transnational lists as they believed that it could make democracy stronger within the EU and help politically unite citizens across the region. In 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron also expressed support for the implementation of transnational party lists.

However, the idea of transnational party lists was halted in the European Parliament in February 2018 during a plenary session vote (when the European Parliament meets as a whole to debate and vote) due to votes against which came from the European People’s Party, the European Conservatives and Reformists, Europe for Freedom and Direct Democracy (which no longer exists as a group), and the European United Left (now The Left Group). For more information about what groups are and how they work in the European Parliament, you can check out this article. It is worth mentioning that it was decided in early 2020 that out of the 73 British seats in the European Parliament, 27 of them would be reallocated to other EU member states and the other 46 will be reserved for any potential new member states in the future.

Arguments against transnational party lists

The arguments against transnational party lists can be seen as representative of the wider supranational versus intergovernmental debate concerning the nature and future of the European Union. The supranational side, those who believe that the EU should have more power and influence that goes beyond the national governments of member states, is more likely to see transnational party lists as a positive necessary change. The intergovernmental side, those who believe that the EU should be mainly a collaboration of member states’ national governments, are more likely to see transnational party lists as unnecessary or even harmful.

For example, the Council of the EU, which is made up of relevant government ministers from each of the EU member states, stated in late 2022 that opposition from most of the member states related to “serious concerns about the respect of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality concerning provisions which go in the direction of establishing a uniform procedure in all member states”. In other words, the Council of the EU expressed concerns that electoral reform procedures proposed by the European Parliament, such as transnational party lists, go against the intergovernmental aspects of the European Union.

The EPP group, which is one of the factions within the European Parliament and currently the largest, argued in 2018 that “transnational lists are neither European nor democratic”. They argued that transnational party lists could “weaken the link between [European Parliament] Members and their electorate”. The EPP is concerned that if there are members of the European Parliament that are elected from voters across the EU rather than from one member state country, it would be harder to hold those members accountable for their decisions. They also argued that having transnational party lists could “strengthen populists” as those “are the ones who benefit from the lack of scrutiny from a defined electorate”. It is worth mentioning that the EPP is one of the conservative groups within the European Parliament and as a result, is more likely to be critical of implementing transnational party lists as it would be a large institutional change.

It is worth noting that there are even arguments against transnational party lists from those who are in favour of a Federal Europe, meaning that the European Union would become more of a federal government like that of the United States. One of these arguments is that transnational party lists “could reinforce the national character” of European Parliament elections. This would be due to voters voting with a ‘European’ mindset when it comes to the transnational party list and with a ‘national’ mindset when it comes to their national party lists. Instead of transnational party lists, it is argued that the focus should be on transnational European parties.

Would transnational party lists make the European Parliament more European and democratic?

After considering all of the above, it is worth asking if introducing transnational party lists would make the European Parliament more European and democratic.

Having a transnational party list alongside national lists could improve democracy within the EU by helping give voters a greater sense that their vote matters within one of the European Union’s legislative institutions. They would be able to cast a vote that could more clearly match what they believe the direction of Europe should be. This could in turn help promote the idea of people across the EU actively seeing themselves as not only citizens of their own countries but also citizens of a greater international organisation.

Transnational party lists might not reduce accountability for EU parliamentarians or promote a national mindset as feared if they are used alongside national lists. Firstly, members of the EU would still be held accountable to their national constituents if they were elected from a national list, or to their wider European constituents if they were elected from a transnational list. Secondly, there is some evidence that European Parliament elections are already seen as less important, with those who do vote tending to vote against their country’s ruling party to express their disapproval (so-called second-order elections). Transnational party lists could change this narrative by helping to present European Parliament elections as not just another way for citizens to express their opinion about the politics of their member state government, but as a way to help shape the direction of a larger political union.

Despite all of this, it is fair to say that transnational party lists cannot act on their own to increase democracy and people’s involvement within the European Union. They can certainly be an important part of a solution that contains other initiatives such as increased outreach and education about the EU and greater youth involvement. In this way, transnational party lists can help make the European Parliament, and the EU as a political level of governance, more ‘European’ and democratic.

Viktoria previously did her bachelor’s in Languages and International Relations at the University of Greenwich in London, UK. She is currently studying for a master’s in European Union Studies at Leiden University.

Image: Shutterstock