The diabolical dilemma for a green future

More mining as a solution but also an obstacle to a climate-neutral 2050.

In 2020, the European Commission presented the Green Deal, an outline of plans for the European Union to halve CO2 emissions by 2030 and even make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. It is an ambitious but also necessary goal as the temperatures on Earth continue to rise rapidly. A key part of the Green Deal is to invest more in renewable energy generated by, among others, wind turbines and solar panels. Sounds like a good idea, but there is a problem; building windmills and solar panels, and storing generated energy, requires batteries. These batteries are produced with so-called rare earth materials, and therein lies the dilemma: where and how do we get these resources?

What are rare earth materials?

There is a wide variety of rare raw materials, each used for something different. For batteries to run your electric car, you need lithium, cobalt and graphite. The solar panels on your roof are made with arsenic, gallium and germanium, and the wind turbines along the highway require neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium. It probably sounds like a lot of abracadabra, but all these raw materials are very important and play a big role in your daily life – even if you don’t have solar panels or an electric car. Just look at your phone, for example; there are plenty of rare elements in that too.

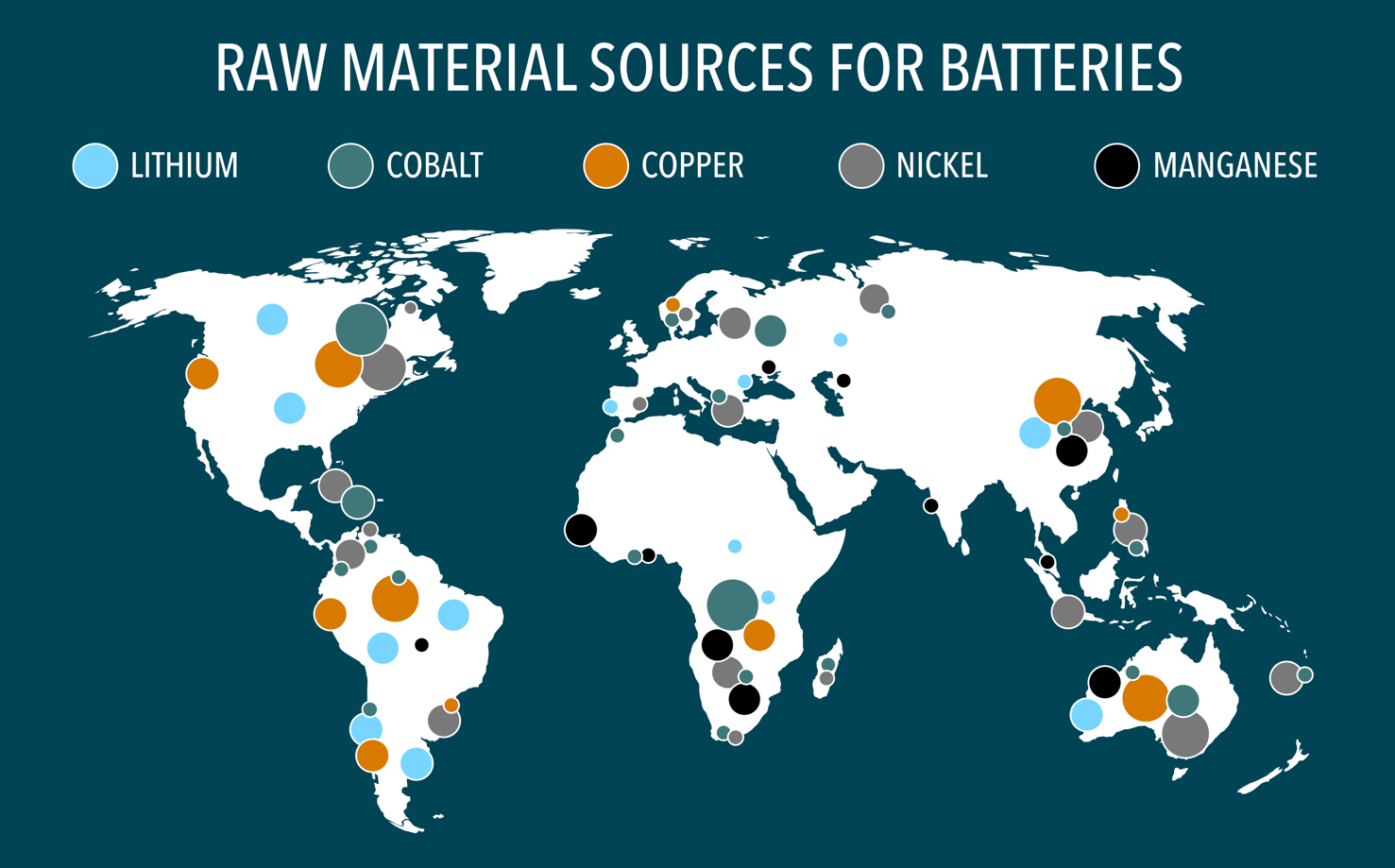

Despite what the name suggests, rare resources are not necessarily rare on Earth. Even in Europe, rare raw materials can be found in several places. The rarity lies in the fact that earth elements are very scattered throughout the earth’s crust and occur in small quantities in many places. In addition, when found, they are difficult to separate from other elements in the ground.

Map of raw material sources for battery production around the world

There are currently two methods used in mining rare earth elements. The first method involves removing the top layer of soil and creating a basin in which chemicals are added to the extracted earth, separating the rare elements from the rest of the earth. However, you can imagine that a pond full of chemicals can cause the necessary damage to nature and leak into groundwater if the basins are not properly sealed. Is the second method a better option then? Probably not. It involves drilling holes in the ground to pump chemicals directly into the earth through PVC pipes and rubber hoses.

Both methods thus create a large amount of toxic waste that can cause great damage to the environment. In some cases, there may even be radioactive residues left behind, as rare resources are often located near the radioactive substances thorium and uranium. The impact involved in mining rare elements is one of the main reasons why raw materials are now hardly mined on the European continent, but this too comes at a high price.

The China issue

Currently, China dominates the market for rare elements. In 2016, the country accounted for 85% of the global supply of raw materials. In fact, the EU is 98% dependent on Chinese production of rare earths. China is not only the world leader in mining raw materials, but also in other parts of the production chain, such as smelting and refining of earth metals. This means it could have huge implications for Europe if China decides to stop exporting rare raw materials.

This near-monopoly on rare resources ensures that China is in a powerful position and has already shown on several occasions that it is not afraid to use this power; for example, in 2010, when the import of rare earth metals to Japan was blocked following the detention of a Chinese captain. While the EU seems to be getting off well so far, there is no guarantee that China will not abuse Europe’s dependence on Chinese raw materials in the future.

Cheap polluting methods and a lack of environmental laws have made China rapidly become the world leader in the rare earths market. For this, however, Chinese people have had to pay a high price. Mining workers often suffer health problems due to exposure to toxic substances. The country also has so-called ‘cancer villages’. These are places where a disproportionate number of people have developed cancer due to pollution caused by mining. One of the most notorious mines in China is Bayan-Obo, with tailings ponds storing more than 70,000 tonnes of radioactive thorium. Recently, these basins have started leaking, resulting in radioactive material entering the groundwater. At some point, this will end up in the Yellow River, a major source of drinking water.

To limit further damage to its own country, China hardly extracts rare earth elements from its own soil anymore. Instead, the country has shifted much of its mining projects to Africa. This can be seen as part of the broader Belt and Road Initiative, China’s foreign policy strategy aimed at cooperation with Africa. The Democratic Republic of Congo is currently one of China’s main sources of rare earth metals, particularly for cobalt used in lithium batteries. In return, China will help improve Congo’s infrastructure and build hospitals. This sounds like a good deal, but the reality is different; in many cases, working conditions in Congolese mines are anything but good. Workers are not properly informed about the fact that cobalt is toxic if you touch and inhale it, with the result that many go to work unprotected.

In addition to dependence on China, the EU also faces human rights violations in Africa. One might therefore wonder whether it is desirable to contribute indirectly to these harsh practices. For many Europeans, however, this is a far-off show. After all, it is hardly ever known where all the raw materials for your phone, solar panels or batteries for your electric car come from.

Europe’s Critical Raw Materials Act

To tackle this raw materials problem, the European Commission introduced the new Critical Raw Materials Act on 16 March this year. The act aims to increase the EU’s self-reliance when it comes to mining, processing and recycling rare earth elements. Specifically, this means that the Commission aims to set up more mining projects within the EU itself. Ultimately, the aim is to have 10% of the total consumption of earth metals coming from European mines and to increase efforts to process these metals in-house. There should also be more investments in diversifying imports from other countries so that there is not a sudden and severe shortage if a country ends cooperation.

Press conference on Critical Raw Materials Act in Brussels on 16 March 2023

Less dependence sounds like a good plan, but one might wonder whether the Raw Materials Act does not go against other important EU goals. Consider, for example, the Nature Restoration Act from European Commissioner Frans Timmermans, which is currently under discussion. Much of Europe’s known reserves of rare earth metals are located in or near protected nature reserves. Therefore, restoring European nature on the one hand and more mining on the other do not go hand in hand, which means difficult decisions have to be made.

Not in my backyard

Besides the fact that mining does not seem to fit into the EU’s broader nature and climate vision, many member states are not keen on opening new mines either. Several EU countries, including Sweden, where a large quantity of rare earth metals was found earlier this year, have enough resources in the ground. However, they face fierce resistance from conservationists and the population living near potential mines. For instance, land in Romania where copper can be found is being bought up by opponents and activities at Serbia’s Jadar lithium mine have been suspended following protests from the population.

Belgrade, Serbia, December 4, 2021. Blockade of state highway E-75

The French town of Tréguennec is located near the second-largest lithium deposit in the country, but there are no concrete plans to mine the “white gold” yet. This would mean digging in a protected nature reserve. Similar situations occur all over Europe, for example in Spain where residents of the Valdeflores Valley have filed a lawsuit against the company Infinity Lithium to stop plans for new mining projects.

Mining in Europe does not seem to be an easy task for the time being; there is a lot of opposition, it goes against other green goals and, even if there is permission, it is likely to take years before a mine will yield anything. In the short term, therefore, there is a need to look outside the European continent for potential partners. One of the plans within the new act involves forming “Critical Raw Materials Clubs” with countries with which the EU already has a close relationship. The most obvious partners would then be Canada, which has a lot of knowledge about processing earth metals, and Australia, which itself has reserves of lithium and other metals.

Another option is to enter into strategic partnerships with African countries, as is currently being done mainly by China. For now, it is unclear how much rare earth metals the African continent has at its disposal. Indeed, there is still relatively little investment in exploring opportunities to intensify mining in Africa. Strategic partnerships and investments in Africa could result in new mining projects that would help solve (part of) Europe’s rare element shortage.

However, Chinese investments in the Democratic Republic of Congo have shown that, if there is insufficient monitoring, there is a risk of exploitation. It is crucial to ensure that Africa does not fall victim to the European demand for raw materials again, as happened, for example, with coal and oil in the past. The World Bank has established the Climate-Smart Mining Initiative to help ensure that resource-rich developing countries also benefit from the growing demand for earth metals and reduce environmental damage from mining projects. Such initiatives are important because many African countries have fewer laws regulating conservation. Europe’s commitment to protect its own nature should not come at the expense of nature in other places.

Investing in innovation

Despite the possibilities of sourcing rare earth elements from outside Europe, the EU also still aims to produce some of the needed raw materials itself. To combine this with other climate goals and nature conservation, it is necessary to invest intensively in research into greener forms of mining. Although mining will always have an impact on the environment, there are several parts of the mining process where investments can be made in green alternatives, such as power and water consumption and the dismantling of the mine at the end of its lifespan. For example, old coal mines in Germany’s Lusatian Lake District have been converted into a nature reserve, which attracts many tourists every year.

There are promising solutions that can make mining cleaner by replacing the chemicals currently needed. One is Phyto mining, using plants that can absorb metals into their tissues. Another example comes from researchers at Harvard University where bacteria have been used to filter earth elements from the soil. For now, these alternatives require a lot of additional research and investment but do paint an optimistic picture for the future. In some cases, rare earth metals could potentially be replaced by more environmentally friendly alternatives. For example, a promising replacement for lithium batteries is being researched; sodium-ion batteries. Sodium can be extracted in large quantities from rock salt and is, thus, potentially a good alternative.

Another option is to focus more on recycling rare earth elements. Currently, there needs to be adequate technology that can be applied to recycling lithium batteries, meaning that empty batteries mostly end up in landfills. For this reason, the EU has made huge investments in supporting the development of technology to make recycling possible.

However, this is not the only aspect of recycling where there is still something to be gained. Parts from old phones and computers, among others, are now only sparsely recycled, partly because the market is currently not set up for it. The focus is still on making devices that can be easily disposed of, not on being able to take apart broken devices or making it possible for consumers to repair parts themselves. Some EU countries already have regulations on recycling electronic waste. For example, in Germany, sellers are required to take back old appliances when consumers buy something new. The aim is to prevent old electronic devices from ending up in landfills.

Tackling the diabolical dilemma

Due to the huge demand for rare earth metals, cleaner alternatives and recycling will not be enough for the time being. Intensifying mining is therefore necessary, whether in Europe itself or beyond. Continuing, in the same way, is not an option, as the war in Ukraine has shown what the consequences can be of over-dependence on one country for crucial raw materials.

This diabolical dilemma shows that the road to a carbon-neutral EU is not completely clean and green. Difficult choices and compromises have to be made. In addition, there needs to be a lot of investment in both strategic partnerships and innovative technologies that can improve the recycling process and help make mining greener. A green future by 2050 is a great aspiration, but we must also commit to making the road towards it as green as possible.

Sabine Herder has finished a master’s in Crisis and Security Management at Leiden University and is currently pursuing a master’s in European Policy at the University of Amsterdam. Before this, she completed a bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a major in International Relations.

Images: Shutterstock