The green world of botanical gardens

The history and current role of botanical gardens, and the mutual cooperation between them.

Exotic plants that you normally never see, the sweet smell in the tropical greenhouses or the special style of a Japanese garden. These are the views that surround you in botanical gardens. But there is more going on in the green world of botanical gardens. For example, there are many collaborations between gardens and they make important contributions to scientific knowledge and the conservation of plants. In addition, botanical gardens have a public function, although as a result, thieves are more likely to be found in the gardens.

Furthermore, the history of botanical gardens will be discussed. This includes the early history of gardens and the emergence of university botanical gardens in Europe. Besides that, we will consider the role botanical gardens played in establishing and expanding colonies. Thus, we will see that botanical gardens have played many different roles over the centuries.

Botanical cooperation: actors involved

Nowadays, there are about nine hundred botanical gardens in Europe. Most European botanical gardens are members of the European Botanic Gardens Consortium (EBGC). Founded in 1994, this organization helps to implement European initiatives and treaties, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity. In addition, the Consortium contributes to the exchange of information among gardens. For example, the EBGC created the International Plant Exchange Network (IPEN) to enable the exchange of plant materials such as seeds, pollen and cuttings between botanical gardens through a registration system. In this way, botanical gardens can expand their collections and more scientists will have the opportunity to study the specimens. The IPEN also has a code of conduct with common policies that member gardens must adhere to. These cover, for example, the acquisition and maintenance of live plant material, the documentation system and the sharing of benefits. Furthermore, the plant material should not be used for commercial purposes. Instead, it must contribute to issues such as scientific research and education. Since these are non-commercial activities, the sharing of benefits usually does not consist of giving money but, for example, a further exchange of plant material, a joint publication of a scientific paper or the sharing of research results.

In addition to the EBGC, there are many other national and international partnerships between botanical gardens. For example, the Dutch Association of Botanical Gardens (NVBT) in the Netherlands, and the Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) that operates on a global level. This is just as well because worldwide there are about 1,775 botanical gardens in 148 different countries. Certain modern techniques are currently used especially in wealthier countries, such as China and countries in the northern hemisphere. Because the costs of certain research are falling, analytical tools are increasingly available and the scientific community is increasingly connected, certain methods do spread. This is conducive to research because it allows for more different plants from various climatic regions to be studied. International cooperation helps create a more level playing field. For example, thanks to training and shared databases, skills and knowledge are better distributed around the world.

Other organizations also play an important role. For example, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an important actor in the global preservation of nature. They manage the list of endangered plant species, called the IUCN Red List. This organization also emphasizes the vital role of botanical gardens, zoos and aquariums in preserving wildlife, fungi and plants. For instance, it mentions that the gardens have led the development and implementation of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation for more than twenty years. This is a program of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity. Based on the idea that without plants there is no life, they seek to slow, and hopefully prevent, the extinction of plants. This has led to the World Flora Online initiative, where one easily gets online access to the most authoritative and comprehensive plant list of vascular plants (seed plants such as herbs and trees) and bryophytes (such as mosses).

In practice, increasing regulation sometimes also leads to the opposite result. For example, plant exchange can actually be made more difficult by the many requirements of actors or the high level of bureaucracy. For example, several biodiversity conventions create so many requirements for the exchange of plants and seeds that it actually discourages gardens from exchanging with other gardens, growers or enthusiasts. One of these requirements is that the country of origin must share fairly in the profits, which can be quite complicated in practice. Examples of how benefits can be shared were mentioned earlier, but it is difficult to assess when, for example, there is a “fair” sharing.

The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (hereafter Kew Gardens), located in London, is the world’s largest botanical garden. Its 120 acres contain more than 8.5 million items. This includes about 95% of all vascular and spore plants (such as ferns). It also includes 60% of known fungal species. In addition to all these plant collections, the garden has a library with the largest collection of published works on botany. In the year 2000, Kew Gardens started the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) project. With a collection of more than 2.4 billion seeds, it is one of the largest seed banks. Of course, they do not do this alone; 97 countries have contributed to this collection. These initiatives are important since about two in five plants worldwide are threatened with extinction. It is hoped that by storing the seeds in seed banks, it will be possible to eventually cultivate them again and reintroduce them to nature, thus preventing their complete disappearance.

The Palm House, Kew Gardens

Public function

Annually, botanical gardens in Europe receive about 120 million visitors. Worldwide, this number is around 200 million. By comparison, national parks attracted about 279 million visitors worldwide in 2011. So botanical gardens can safely be called popular, and not surprisingly so. The gardens offer the public the opportunity to learn about special collections and the knowledge gained by scientists in an accessible way. Many botanical gardens pay attention to this education. Moreover, this way people can see specimens of plants for which they normally would have to travel to the other side of the world. Furthermore, it is a peaceful environment where you can often feast your eyes. Except when the Amorphophallus titanum (called the titan arum or “corpse plant”) blooms, because then the whole tent smells like sweaty feet or even rotting flesh….

That some plants are worth a lot has also caught the eye of the black market. For example, a very rare water lily, the Nymphaea thermarum, was stolen in the Kew Gardens in 2014. Unfortunately, the police failed to recover the plant. The remaining lilies are well-guarded. Kew Gardens, by the way, has had its own police unit, the Kew Constabulary, for more than a hundred and fifty years, overseeing the security of the gardens. Initially, they even had the same powers as the Metropolitan Police. Nowadays, with twenty officers and one car, the unit is the smallest police unit in the world. They said goodbye to their own fire department a century ago.

One of the gardeners at the Sir Harold Hillier Gardens in Hampshire, England, also indicates that thefts occur regularly. She says that their records show that about ten to twenty plants are stolen each year, although, in reality, the amount will be higher. For example, hundreds of bulbs of new varieties of snowdrops had been stolen. These bulbs were worth around one hundred pounds per bulb. The remaining bulbs have been stored and are on limited display.

Nymphaea thermarum, the smallest waterlily

Emergence of botanical gardens

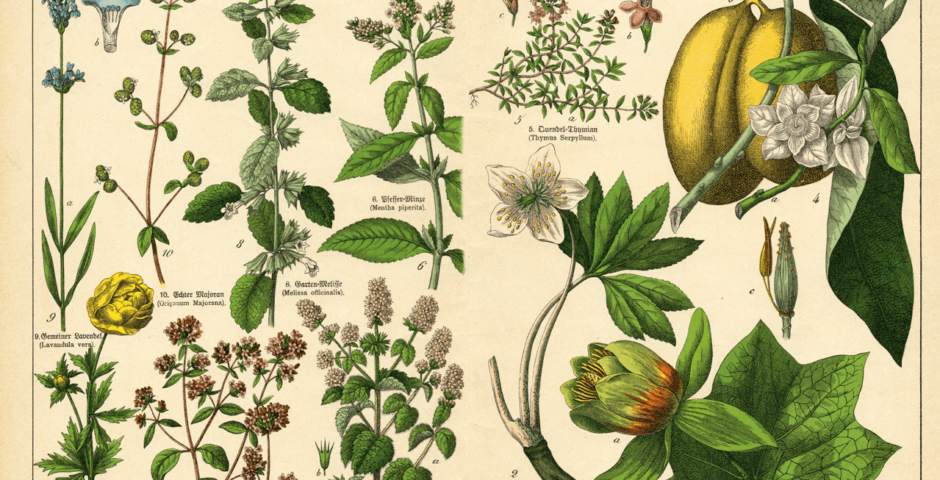

Sir Arthur William Hill (1875-1941) was the director of the aforementioned Kew Gardens. He once wrote that there are three things that once drove mankind to undertake distant journeys: gold, spices and medicine. According to him, the last two can be linked to the creation of botanical gardens. The search for herbs gave rise to the creation of some botanical gardens in the tropics, while the need for medicine in Europe itself was the trigger. Monks, or later medical students, could examine plants with medical properties in the gardens.

The roots of large gardens intended for the public or for research go way back. For example, the system we use to classify plants was already devised by the ancient Greeks. There were also gardens with some aesthetic or economic value at that time. The oldest known garden dates back to about 1000 BC, namely the Botanical Garden of Thutmose III in Egypt. Some historians argue that there were several gardens of purely aesthetic value in Egypt as early as 2000 BC. The Chinese were also early adopters, making distant journeys millennia ago to collect unusual and medicinal plants. This took place as early as around 2800 BC.

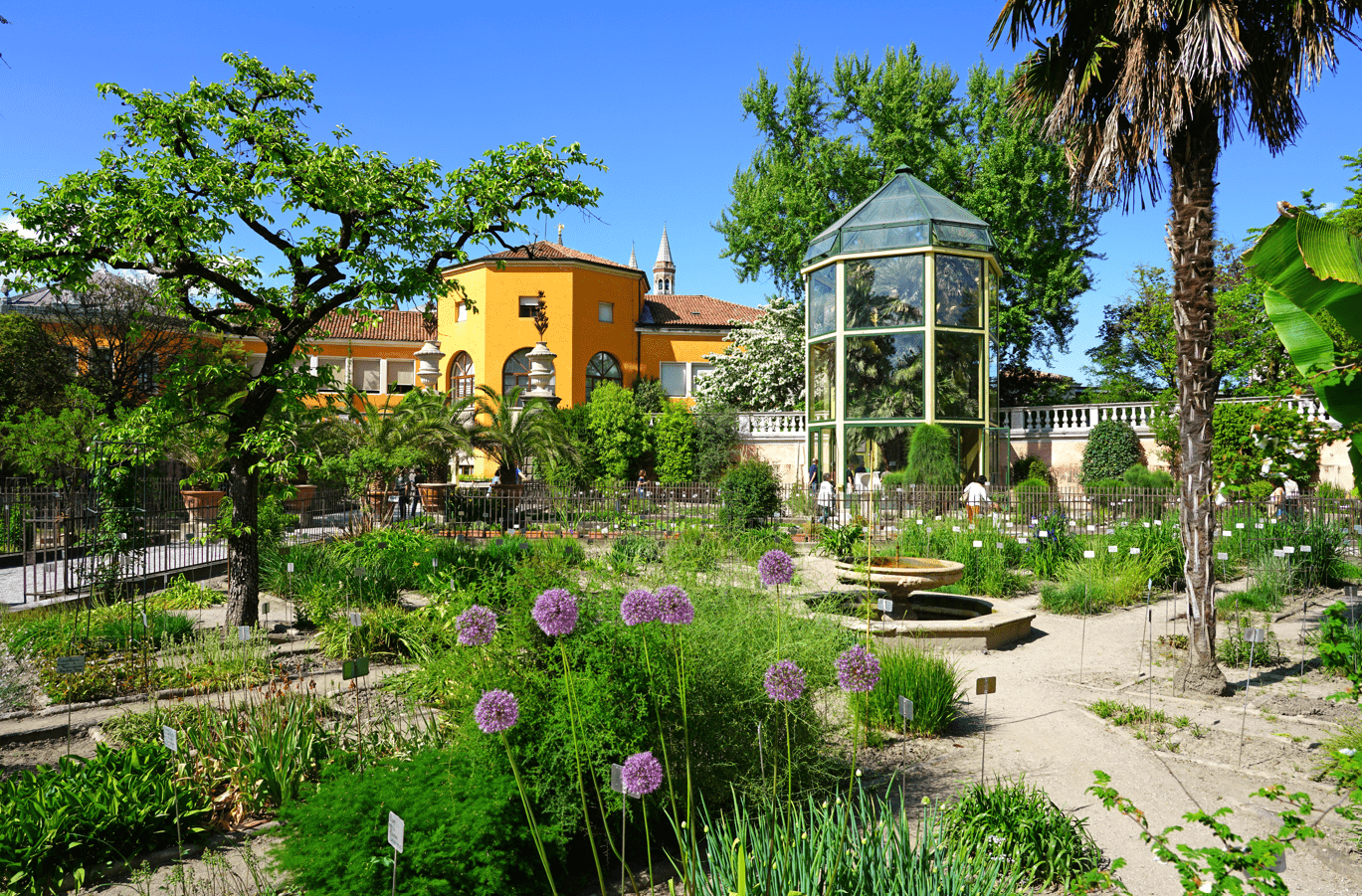

The botanical garden of Padua, Italy, from 1545, is the world’s first, still existing, university botanical garden. The garden was created in order to allow medical students to study medicinal plants. This was done at most emerging European universities at the time. This often involved a bit of copying from the Garden of Padua. Today, the garden also has a section with poisonous plants, since in small quantities these can actually have a healing effect as well. The layout of Padua’s botanical garden shows that plant theft is not just something of the present day. In fact, the regular theft of rare plants was one of the reasons why a wall was soon erected around the garden. The penalties for plant theft were not mild and could include a fine, imprisonment or even banishment.

Orto Botanico di Padova (University of Padua Botanical Garden)

Botanical gardens and colonialism

Botanical gardens also contributed to some extent to the establishment and expansion of colonies in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Imperial botanical gardens, for example, provided plant transfers and scientific plant development, leading to new plantation crops for the tropical colonies. Central to the British imperial network of botanical gardens were the Kew Gardens. There, among other things, scientists were engaged in studying and developing improved species and cultivation methods. This knowledge eventually reached growers through the network. Around the year 1870, for example, botanical gardens were established in Wellington, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Cairo, Durban and Buenos Aires. According to some scholars, botanical gardens were a crucial factor in the success of the new plantation crops and the industry surrounding them. This in turn was a very important source of income and wealth of the empire.

For example, rubber plantations were established in the British colony of Malaya (now Malaysia) with seeds sourced from Brazil. As original nature was replaced by monocultures, this was at the expense of biodiversity. Another example is the development of quinine, derived from the bark of the Cinchona tree that grows in the Andes. Indeed, quinine is an effective malaria drug and is still used today in the treatment of malaria. Several gardens, including Kew Gardens, collected specimens of the bark to better understand the botany of the tree. A special heated greenhouse was even built at Kew for it. The strongest varieties were selected for cultivation. At first, the resource was scarce, but eventually, the British and Dutch established entire quinine plantations. Because Europeans gained reliable and cheap access to quinine, they were able to colonize Africa and India on a large scale. Indeed, the drug increased the survival rate of Europeans travelling to Africa and India. Tonic was made from the quinine; the bitter taste of the drink came from the quinine. The British tried to moderate this bitterness by adding water, sugar, lime juice and gin. That’s how the gin tonic was born.

We have seen that botanical gardens have played many different roles over the years. In the past, gardens contributed to the reduction of biodiversity. Indeed, with the rise of plantations, forests and other natural areas were replaced by monocultures. Now, on the contrary, much attention is being paid to issues such as biodiversity, ecosystems and plant conservation. Botanical gardens play an important role in preserving plants threatened with extinction and increasing knowledge about the themes just mentioned. International partnerships promote these activities. Thanks to the accessibility of botanical gardens, a wide audience can learn more about plants, and admire their diversity. Still a good thing, then, that botanical gardens keep up with the times.

Julia is studying Notarial Law at Utrecht University. She is also studying Liberal Arts and Sciences, with a major in International Relations in Historical Perspective.

Images: Shutterstock