The dissolution of Nagorno-Karabakh

The contextualisation of the conflict between Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh.

On 19 September 2023, Azerbaijan launched an attack on the ethnic Armenian enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan claims it did this after four Azerbaijani soldiers and two civilians were killed in the enclave that same month. A ceasefire was declared rather quickly after the attack, so the outbreak of violence can be seen as a one-day war. On 29 September, Samvel Shahramanyan, the president of Nagorno-Karabakh, announced that the government and all state institutions of the enclave would be dissolved from 1 January 2024. This effectively means that the enclave will cease to exist. Meanwhile, a huge refugee influx towards the neighbouring country of Armenia emerged. Of the estimated 120,000 inhabitants of the enclave, only 50 to 1,000 were left on 2 October, the United Nations (UN) concluded.

You just read in one short paragraph how a globally little-recognised republic announced its dissolution. As you probably understand, this explanation is not very detailed and there is a lengthy history of this conflict. This article therefore aims to provide more context to the reports on the conflict that dominated the news but which also quickly faded into the background. This article looks at the history of the conflict, but also at the other countries that have a seat at the table and why international action in the region has largely failed to appear.

Background to the conflict

The Soviet Union founded the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast in the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic in 1923. At that time, the population of the oblast consisted of 95% ethnic Armenians. In the Soviet Union, an autonomous oblast was a kind of province. When a republic had a region where the majority of the population had a different (ethnic) nationality from that of the republic within which they were located, they were sometimes converted into this kind of province. This title gave the region an autonomous status within the republic. Another example of a former autonomous oblast is the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, today known as the self-proclaimed Republic of South Ossetia. This is a region also characterised by conflict to this day.

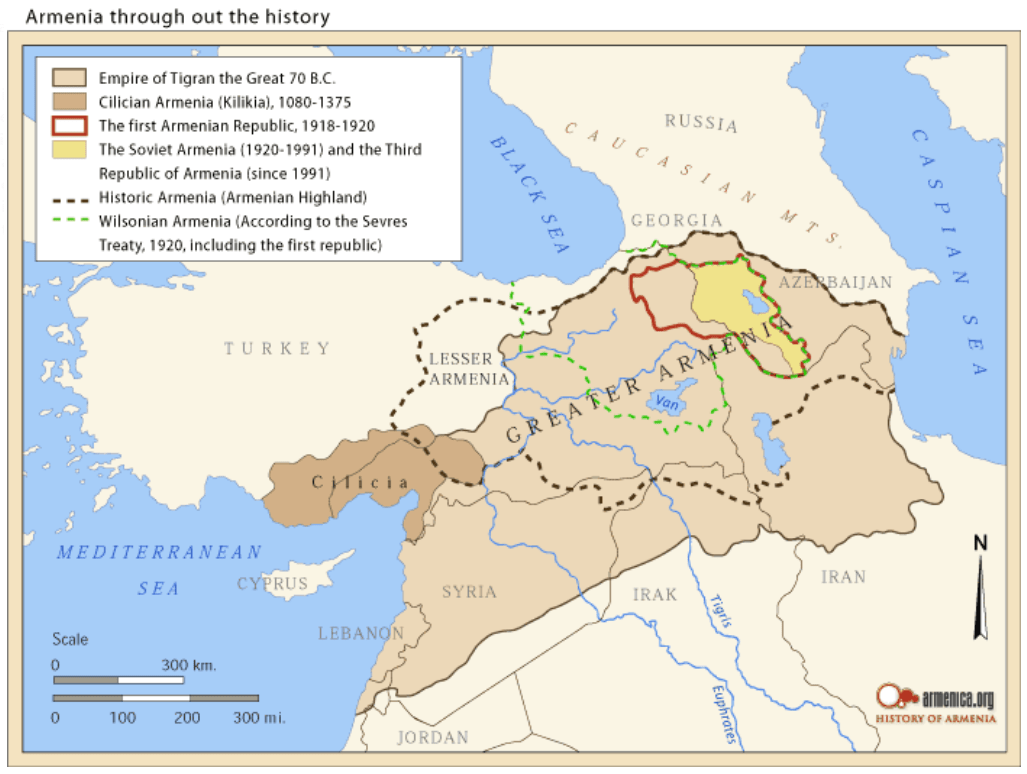

The large presence of Armenians in the enclave shows that we have to go even further back in history to get the necessary context. In 1454, Armenia was divided into the Ottoman Empire and the Persian Empire. The Ottoman part became known as Western Armenia, while the Persian part was called Eastern Armenia. In 1828, Eastern Armenia was conquered by the Russians and thus became part of the Russian Empire. During the period when the Russian Empire dominated both present-day Armenia and Azerbaijan, the Russians promoted the influx of Armenians from Iran to the region we now know as Nagorno-Karabakh. At the very same time, many Azerbaijanis fled from the region to Iran. It is therefore important to note that Armenians are traditionally Christian (Armenia was the first country in the world to make Christianity the state religion in 301 AD) and Azerbaijanis are traditionally Muslim. The map below shows a bit more clearly what Armenia looked like throughout history.

Armenia throughout history

Between 1918 and 1920, the Armenian-Azerbaijani War took place, characterised by a series of conflicts spread across the region. At that time, Armenians made up one-third of the population. In 1918, Armenia proclaimed an independent state there, which was undone by the Ottoman Empire. After the fall of the empire, the British occupied the area and appointed a governor-general supported by the Azerbaijani government. In 1920, the area joined Armenia. Meanwhile, both Azerbaijan and Armenia were conquered by the Red Army (the army of Bolshevik Russia). To gain support from the Armenians, the Red Army granted Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, along with Nakhchivan (now an Azerbaijani autonomous republic not bordering the rest of the country) and Zangezur (still a province of Armenia, now called Syunik).

However, this allocation took place under the Red Army and not under actual Soviet rule. Indeed, with the creation of the Autonomous Oblast, the administration of the region was still placed with the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic, as mentioned earlier. It was Stalin who reversed the decision. Only Zanzegur was given to Armenia. Several theories explain as to why he would have done so. One of them would be to “bring in” recently emerged Turkey so that it also developed along communist lines. Either way, this decision does account for the fact that Nagorno-Karabakh came under Azerbaijan’s administration as an autonomous oblast, and is thus also one of the main roots of the current conflict.

The revival of the current conflict

We are not done with the Soviet history lesson yet. Even with the revival of the current conflict, we need to dive a little deeper into what went on within the state administration at the end of the Soviet Union. In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became the new leader of the Soviet Union. His reign was marked by the fall of the Soviet Union, but also by what we call Glasnost and Perestroika, or openness and reform. Perestroika is the term used for Gorbachev’s reform policies that focused on state and economic reforms. Glasnost was supposed to contribute to those reforms by making the state’s actions more open. It was this Glasnost and Perestroika that caused the rise of ethnic nationalism among the various peoples within the Soviet Union, including among Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh.

In 1988, the Nagorno-Karabakh government passed a resolution declaring its intention to join the then-still Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. This resolution created tensions between the two socialist republics of Azerbaijan and Armenia, but during the time of Soviet rule, armed clashes between the two remained relatively under control. However, this did not mean that there was no violence. The start of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, which officially ended in 1994, is therefore placed in 1988.

In 1991, the Soviet Union and the various Soviet republics collapsed. Both Armenia and Azerbaijan became independent, each forming a republic. Nagorno-Karabakh also declared itself independent after the fall of the Soviet Union. With the collapse of the Soviet Union the control over Armenia and Azerbaijan disappeared. This, together with Nagorno-Karabakh’s declaration of independence, was the recipe for so much violence that it turned into a total war between, initially, Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh. Later, Armenia also got involved.

The First War lasted until 1994, when the Bishkek Protocol was agreed on, establishing a ceasefire. This declaration was signed by Armenia, Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh and Russia. The ceasefire was violated several times, including in 2016. A four-day war took place from 1 to 5 April 2016, the fiercest outbreak of violence since the 1994 ceasefire. Azerbaijan officially lost the First War. This defeat created a strong anti-Armenian sentiment in Azerbaijan. In 2020, the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War broke out due to fighting that erupted at the Azerbaijan-Nagorno-Karabakh border, as agreed in 1994. The war officially lasted from 27 September to 10 November 2020, and it again came to a ceasefire led by Russia. Both wars, as well as outbreaks of violence in between, left tens of thousands dead.

The dissolution of Nagorno-Karabakh

It has already been mentioned a few times in this article, but Nagorno-Karabakh is hardly recognised worldwide. Even Armenia does not recognise the enclave as an independent state. This is mainly due to not wanting to stand in the way of peace negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Nevertheless, three places do recognise the enclave as independent: Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Transnistria. Abkhazia and previously mentioned South Ossetia are regions that lie within Georgia’s territory. Both regions have declared themselves independent, but are also hardly recognised (albeit by more countries than Nagorno-Karabakh). Transnistria is in Moldova and borders Ukraine. Transnistria has also declared itself independent and, like Nagorno-Karabakh, is only recognised as an independent state by a few other limited-recognised enclaves.

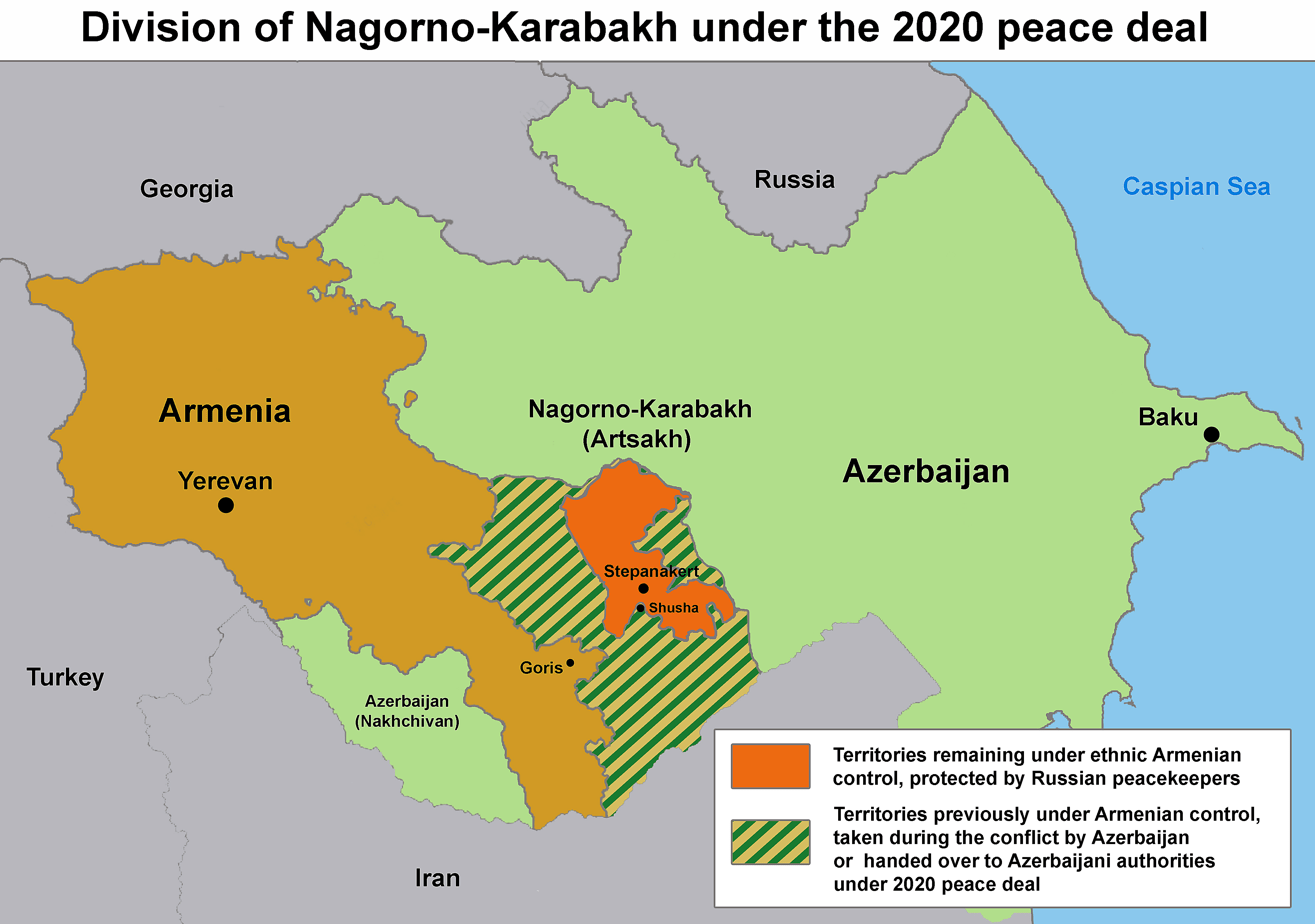

The map below shows the division of territory at the end of the Second War in Nagorno-Karabakh. An important place to highlight is the Lachin corridor. This was the only connecting road between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh before the Second War. After the war, however, it was assigned to Azerbaijan and Russian peacekeepers were supposed to guard the corridor, but in practice, this was hardly done. After all, according to Amnesty International, Azerbaijan blocked this access road after the war, causing a shortage of food, medicine and fuel in the enclave. This blockade began in December 2022. A checkpoint was placed in April 2023. Finally, Azerbaijan closed the corridor completely in June of this year. Already before the outbreak of the most recent fighting, this blockade was called an attempted genocide by former First Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court Luis Moreno Ocampo.

Division of Nagorno-Karabakh under the 2020 Bishkek Protocol

The blockade has weakened the enclave. Before the dissolution of Nagorno-Karabakh was announced, talks between the leaders of the enclave and Azerbaijan took place during the ceasefire. From the Azerbaijani side, promises were made to the enclave’s leaders. For instance, Armenians in the enclave would be granted voting rights in Azerbaijan. However, doubts surrounding the promises were too high. It is therefore good to take a step back for a moment and refer to the end of the First War and the anti-Armenian sentiment that arose after Azerbaijan had lost the war. This anti-Armenian sentiment led Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh to fear oppression by the Azerbaijani administration. With the influx of a huge number of Armenians from the already weakened enclave, the Nagorno-Karabakh administration eventually decided on the current state of affairs: to dissolve the enclave by 1 January 2024.

The role of the international community

The most obvious country that has a seat at the table is Russia. Russia and Armenia are officially allies. This is reflected in part by the fact that they are both members of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) which has its origins in 1992. This is a military alliance between Russia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Belarus. It can be seen as a counterpart to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). This means that Russia supports Armenia militarily; for instance, Russia has a military base in Armenia. Another example reflecting the alliance between the two is the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) of which they are both members. Also, as mentioned earlier, Russia is present in Nagorno-Karabakh as a peacekeeping force.

However, it has become apparent, with the failure of Russian peacekeepers to monitor the Laçhin corridor, that, in reality, Russia is not necessarily a good ally . One reason for this is the war in Ukraine. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine started on 24 February 2022, Russia’s attention has been focused on this war rather than what is happening in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Two other key allies of Azerbaijan are Türkiye (previously known as Turkey in English) and Israel. Türkiye previously supported Azerbaijan in the 2020 war. The alliance between the two countries goes back to the peoples’ roots. As mentioned earlier, the Azerbaijani people are originally Turkic people. In addition, the aforementioned Armenian Genocide contributed to the bad relations between Türkiye and Armenia. The second alliance has to do with another ally of Armenia and vice versa: Iran. Israel dislikes Iran, an ally of Armenia, and so they support Azerbaijan. In addition, Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, has traditionally had a Jewish population. While Azerbaijan’s population is largely Muslim, the state is secular so followers of other religions can live comfortably. Finally, Azerbaijan is also important to Israel, since as much as 40 per cent of Israel’s oil needs are met by Azerbaijan.

The role of the European Union

The European Union (EU) and its member states, like much of the international community, do not recognise Nagorno-Karabakh as an independent state. Nor is it an ally of Armenia or Azerbaijan. Nevertheless, it is important to consider the EU’s attitude towards the two countries. Firstly, this has to do with the war in Ukraine. At the beginning of the war, you could read an article on Shaping Europe about the EU’s dependence on Russia when it came to gas. Since the war broke out and there are sanctions against Russia, the EU has had to seek gas from other sources. One such source is Azerbaijan.

The share of Azerbaijani gas in Europe’s total gas consumption has increased from two to three per cent since 2021. Of course, this sounds like a small growth, but that is why it is important to put it in context. Namely, the EU is distancing itself from Russian gas because Russia invaded Ukraine. So a small part of the gas demand previously supplied by Russia is now met by gas from a country that maintains a blockade on food, fuel and medicine. Getting gas from Azerbaijan, for example, was therefore condemned by 50 French politicians back in 2022 in a letter to the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen. They found it hypocritical that the EU swore off retrieving gas from one aggressor but then proceeded to retrieve gas from another aggressor without any hesitation.

Quite soon after the ceasefire and the arrival of 100,000 refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia asked the EU for help. This mainly involved temporary shelters (for example tents) and medical equipment that the EU could provide. Rather quickly after the start of the flare-up of violence in Nagorno-Karabakh, the European Commission announced that it was increasing humanitarian aid by five million euros (eventually this was increased by an additional five million), both for refugees in Armenia, and vulnerable people still in the enclave. In addition, the EU is sending several aircrafts including food, hygiene products and tents to Armenia. The EU may not be taking sides in the conflict, but by both supporting Armenia and taking gas from Azerbaijan, it is sending mixed signals for sure.

Is it over now?

The question is whether, with the dissolution of Nagorno-Karabakh on 1 January 2024, the conflict will then really be over. Azerbaijan has called for Nagorno-Karabakh to be fully integrated into Azerbaijani society, so it is unlikely that the region will retain a separate status. On the other hand, Armenians fear that, with the dissolution of the enclave, Azerbaijan is not finished and wants to move further across the Armenian border. A long-standing strategic goal of Azerbaijan is to connect the country with the autonomous republic of Nakhchivan but also to go even further and seek a connection with Türkiye and the Mediterranean Sea. “The tail” of Armenia, the Syunik region, is the only thing standing in the way of this connection. Already since 2020, Azerbaijan has troops stationed near the border with Armenia close to Syunik. Thus, in short, it remains to be seen what exactly will happen on and after 1 January 2024.

Want to know more about the Second War in Nagorno-Karabakh and its aftermath? Then I can recommend checking out the documentary 1489. This documentary was made by the Armenian Shoghakat Vardanyan using only her iPhone. In the film, Shoghakat shows her life and that of her parents from day seven of the war, the day her brother went missing. At that time, he was fulfilling his military service in Armenia’s army. His body was found, but it took over a year and a half before it was actually identified. Prior to identification, the number 1489 was assigned to his body, meaning “body of an individual missing in action”. The film premiered at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) and also won the award for best film, which Shoghakat accepted in person.

Header image: Shutterstock, the photo depicts the monument Menk’ enk’ mer leṙnerə (We Are Our Mountains, also known as Tatik-Papik, Grandmother and Grandfather). The monument stands just outside Stepanakert, the town considered the capital of the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave. The monument depicts an old man and woman rising from the earth, symbolising the bond between the people of Nagorno-Karabakh and the mountainous land where they live.

In-text image #1: Armenica.org

In-text image #2: Shutterstock